Bernard is a novelist and a painter. He has written five novels; his most recent book is a book of short stories called “When I Saw the Animal” (2018). He considers writing to be a vocational pursuit but drawing and painting are an immersive activity, “a relaxation in a highly concentrated way”. Below is Bernard’s own story of the art work he has submitted.

At that time, Bernard walked a great distance every day, and usually well into the night. Perhaps the goal of all this walking was to try and find equilibrium, as if each leg were a pendulum and the Earth twisted this way and that as he swung his legs above it. Other than the necessities of work, it was his principal pursuit. He imagined that most pursuits had goals. He also imagined that walking was a pursuit rather than a compulsion. This mischaracterisation sometimes erased itself at one or two in the morning as he passed other night-people down by the bay.

If you navigate using some mapping apps, they offer you the chance to re-centre, and this still seems apt to Bernard. In walking, there was no destination, but only what zoologists call the range – in Bernard’s case three or four kilometres in all directions, with occasional longer deviations.

Bernard had taken up painting by default, using his daughter’s left-over paints.

Bernard sought subject matter less directly confronting: seascapes; his nephew as the Blue Boy; his daughter in Leonardo’s colours. Many writers and artists in mourning seemed to be able to address the source of their grief directly, portray both the grief and its object, but he couldn’t bring himself to write about or paint his son. It is now fifteen years since JoJo passed away.

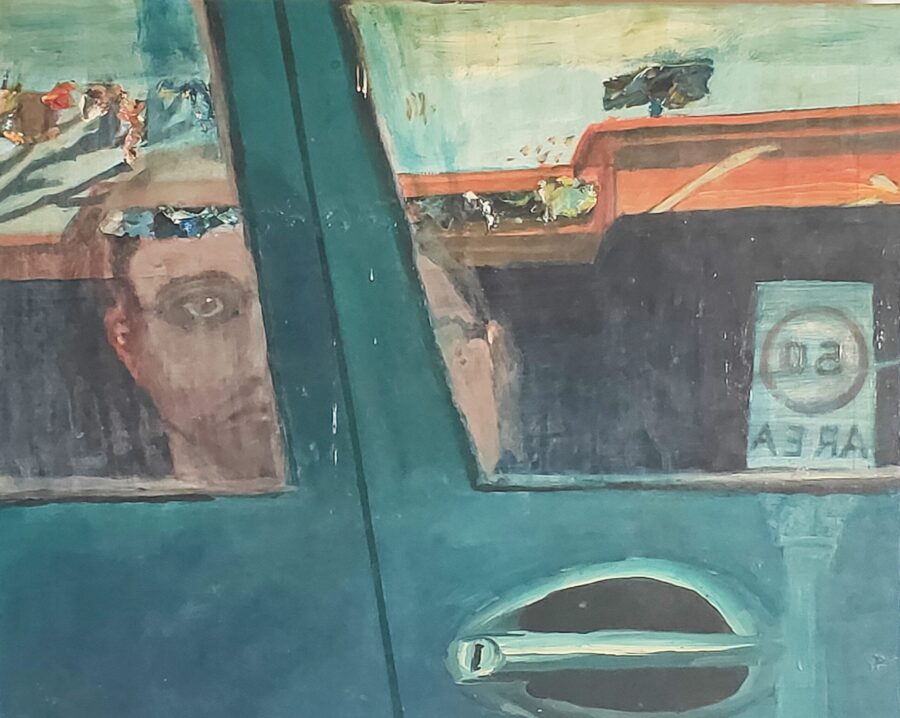

On these walks, Bernard took dozens and hundreds of photos using the camera in his phone, and if they were bad enough, they could form the basis of paintings. ‘Self-portrait on Marion Street’ was based on four or five particularly poor photos from an afternoon walk around his neighbourhood. It was mid-winter about eighteen months after he began to paint.

The painting built up several layers of acrylic and media, and he also collaged some paint scraps into it to bring some roughness into it; he didn’t want it to be an entirely smooth self-portrait.

Time in grieving has a different meaning to lived time. Grieving time stretches out in all directions and also compresses the day into a single repeated moment.

In the painting, Bernard tried to deal with that symbolically: for example, under a 50km/h speed limit sign, instead of the actual metal pole, he painted in a Corinthian column that’s supporting the (unthinkably fast) speed limit. This seemed inadequate symbolically, but he left it there as he liked the neo-classical look of it. (Another painting from around that time is titled ‘Self-Portrait in a Goya Landscape’.)

Non-classical buildings in the background towered over the composition – non-classical meaning, in this inner-west context, late-60s brick veneer. The buildings appeared in the worst photograph of the five, which showed a filthy car, covered with thick, rough chevrons of mud. He’d noticed his reflection in this old car – the angles were strongly distorting, so that suited him well. In the painting, he altered this so that in one of the two halves of him he appeared wearing glasses and in the other without, as though one of him was trying to see through a clear lens and the other deliberately avoided possible clarity.

This year, as the pandemic spread (and continues to spread) throughout the world – ridden by ubiquitous expressions of grief and panic, anger and resistance – what most came to Bernard was a sense of familiarity. Weirdly, and with some guilt, he found the lockdown healing: it made new and gentle sense that hyper-vigilance and lockdowns had been traumatic. From experience, he felt as though he knew how to live in this time.

Grief is so overwhelming that all one can do is to keep going. Bernard (of course) doesn’t believe it is something to get over or something that you ought to get over, but it is something to live with and through. The Jewish rituals of mourning were helpful to him, and a creative practice was too. Bernard found – and were he to give advice to those struggling with grief or depressive debilitations, this would be it – if it is possible to undertake one thing in a day, one task or piece of work, no matter how small, it stays done. As you re-emerge into the world it is there waiting. It may not be possible every day, but be gentle with yourself and see if you can: a sketch, a few words, a few minutes with music. It might be to do some sort of regular household function; looking back on it, that’s one thing that you have done in the day, and once you’ve done something and even though you’re not fully in the world, you’ve still managed to participate in some way. It still manages to help in some way.

Walking can help, too.

Bernard Cohen- photographer Mira Lemberg

More of Bernard’s work can be found at http://www.bernardcohen.com.au/