Interdisciplinary artist Erica Seccombe discusses her fantastic work creating a series of original illustrations for the Campbelltown Hospital Rebuild. Her large-scale artworks feature plants native to the Macarthur region and were created with extensive consultation with the Campbelltown community. As part of her creative process, Erica hosted free drawing workshops for the Campbelltown public and took place in knowledge-sharing with Elders Aunty Deidre Martin, a Walbanga woman of the Yuin Nation, and Aunty Glenda Chalker, a Dharawal woman of the Cubbitch Barta Clan. Her art highlights the role that connection to nature and place can play in bringing together diverse cultures and communities.

To hear more about this project and hear community voices involved in all projects, please view https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f1Z35dTjsCk&t=181s

What does a hospital feel like?

The leading question, ‘What does a hospital feel like?’ is the title of one of the projects that engaged with the diverse communities from the Macarthur Region in NSW to develop an art strategy for the Campbelltown Hospital Rebuild. Initiated by NSW Health and the Campbelltown Arts Centre, it places community, culture and creativity at the heart of the Stage Two redevelopment of the Campbelltown Hospital. Facilitating this project as the principal artist, I was commissioned to provide creative solutions that involved the community in the redevelopment in active, creative and meaningful ways. It is informed by the South Western Sydney Health and Arts Strategic Plan, 2018-23, with the “belief that arts and creativity move minds, bodies and spirits towards sustaining healthy lives.” This project has been conducted through a consultation process, where I have worked closely with the art strategy steering committee that includes representatives from Campbelltown community groups, Campbeltown Arts Centre, Arts & Cultural Liaison Officer, Health Infrastructure, construction managers and the architects Billard Leece Partnership. There are many important outcomes of the overall art strategy consultation, but one main element that I describe here has resulted in a suite of original illustrations depicting a selection of native plants that will now feature as a continuous story throughout the brand new hospital building. Beginning with the premise that being in contact with nature may relieve some of the stress of a hospital experience, this selection of plants endemic to the region has cultural significance to First Nations people. The Campbelltown Hospital is situated on the custodial lands of the Dharawal where there are many reminders of their traditional and ongoing connection to the land.

To meet the demands of high regional growth, the $632 million Stage Two of the Campbelltown Hospital Redevelopment includes a multi-storey acute service building with new inpatient wards, ambulatory, outpatient, allied health services, pathology and clinical information. The project, ‘What does a hospital feel like?’, considers that while much research has been undertaken in the design of hospitals, there is still a need to understand the concept of ‘feelings’ when patient and staff use the service. A large amount of effort is focused on the practical design of the main clinical functions of the hospital, yet a significant physical imprint of the hospital ‘non-spaces’ such as corridors, retail and entrances can also form a critical part of creating a sense of place and local identity. This project has been a rare opportunity to start the community consultation at the very beginning, and in doing so it has reached its goal to provide opportunities for extraordinary, memorable positive encounters for patients, carers, community and staff, regardless of age, cultural identity, gender or ability.

Interdisciplinary practice

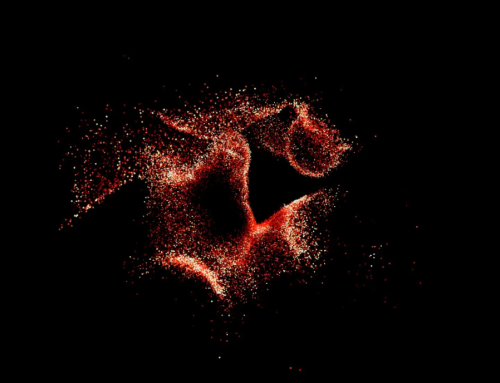

My art practice spans traditional and photographic print media and drawing though to experimental digital platforms using frontier scientific visualisation software. Through my practice I explore the use of scientific technology, such as microscopes and X-ray, investigating our perceptions of the limits of nature to begin to explore questions about ourselves and our experience of the world. By addressing issues around art and nature, scientific imaging and knowledge, I am interested in individual and collective experiences of connecting with nature, real or artificial, particularly in an era facing environmental crisis and uncertainty. A key concept I have pursued through my art practice is to test if nature must be real to benefit from it. As an example, Edward. O. Wilson’s Biophilia (1984) is a hypothesis proposing that humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections and affiliations with nature and other forms of life. In Technobiophilia: nature and cyberspace, (2013) Sue Thomas discusses how encounters with ‘real’ nature have long been proven to be psychologically beneficial but how the experience of nature in a ‘virtual’ situation can be just as profound as the real thing. This argument explores the idea that because an increasing number of people now live in built environments and have less opportunity to interact with nature, experiences that evoke virtual contact with nature are equally affecting. My first response to the project brief was therefore to question how nature as a concept or design can contribute to and promote a feeling of individual and collective restoration and wellbeing in the hospital spaces. This is particularly important as an awareness of nature can be a strong connecting thread across diverse cultures and communities.

Workshops and process

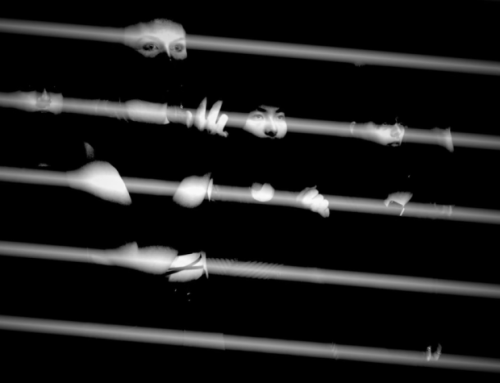

Acting on this, I initiated a series of free public drawing workshops conducted at Mt Annan Botanic Gardens, at Campbelltown Arts Centre and at the Campbelltown Hospital. This enabled me to meet and work with diverse groups of people from the Macarthur community including hospital staff and patients of all ages.

These open workshops have been instrumental in exploring creative solutions to the question, ‘What does a hospital feel like?’ In my workshops I employ methods that encourage participants with little or no experience of observational drawing to create works of art inspired by various plants specimens, seed pods and other natural forms from the local vicinity. I intentionally provided a specific range of materials and drawing tools, such as colourful water-based ink, wide brushes and soft sponges, which reduce an individual’s ability to make highly detailed drawings. Participants draw more freely without the pressure and expectation that their drawings must be perfectly rendered. I also included the opportunity to experiment with a range of digital and analogue microscopes. These drawing techniques, in combination with the use of lenses, enables people to investigate and draw plants from a different perspective, while learning new skills and building confidence. This act of collective looking encourages the groups to share their views through the microscope, and create conversation and make connections. Participants were invited to contribute their drawings to the project, and these have created a unique suite of images as part of the art strategy for the new mental health level.

Participants across all the drawing workshops strongly believed that incorporating illustrations of native plants into the hospital would enhance a sense of wellbeing, uniting visitors with the surrounding environment, sharing respect and acknowledging First Nation heritage. This outcome directed the next stage of the consultation project. Here I had the opportunity to meet and learn from an Elder, Aunty Deidre Martin, a Walbanga woman of the Yuin Nation, and Elder Aunty Glenda Chalker, a Dharawal woman of the Cubbitch Barta Clan. On a walk to Minerva Pool, a sacred women’s place for the Dharawal People, Aunty Deidre introduced me and members of the steering committee to culturally significant plants, generously sharing her knowledge of their traditional uses and meanings. This was followed by a consultation process with both Aunty Glenda and Aunty Deirdre, where they established which plants were most appropriate for the many public levels of the hospital’s interior. Because of my European heritage I felt conflicted, in that any representative drawing I make of these plants could be viewed as another form of colonisation. Aunty Glenda put me at ease by advising me that the illustrations of the included plants should be easily identifiable to everyone, no matter what their heritage. Through this I have learned that the act of sharing knowledge cultivates inclusivity which supports empowerment, acceptance and cultural pride which contribute to a positive healing environment for First Nations People and for the wider community.

The ten plants selected as part of the art strategy will feature as large-scale artworks on each level and will be applied to different interior spaces. they include the plants Lomandra longifoilia, the spiny-head mat-rush or basket grass. In Dharawal, wadgamari biyangalaywala means, “used to make grass baskets.” Spiny-head mat-rush has multiple uses; the seeds and roots are a source of food, and the strappy leaves are woven to make strong durable bags, string, nets, and tools.

Melaleuca linariifolia is the flax-leaved paperbark, known as Gurrungurrung in Dharawal. Rich in essential oils, melaleuca flowers, leaves and bark have important antiseptic and antibacterial properties, but are also useful for making shelters, tools and fire. Lambertia Formosa, or guridja in Dharawal, is referred to colloquially as the mountain devil because of the horn-shaped seed pods. It is also called the honey flower and is known as a source of nourishment. Smilax glyciphylla, or sweet sarsaparilla is used for a range of bush remedies because of its antioxidant and antiscorbutic properties, but should not be confused with a similar vine called Hardenbergia. On the street level of the hospital in the main foyer, a feature wall will incorporate all these plants together in a hand painted mural.

This expansive artwork will wrap around the interior as visitors move from one space to the next, reflecting the overall art strategy for the whole hospital. Historically, gardens have always been considered a place of healing, and the importance of our natural ecosystems remains relevant to us all, and to the health and happiness of future generations. I feel personally enriched by this experience, and I look forward to seeing the new hospital open in 2022, knowing that the Campbelltown community will share an incredible sense of pride in how safe and inclusive they have made this new welcoming hospital feel.

This expansive artwork will wrap around the interior as visitors move from one space to the next, reflecting the overall art strategy for the whole hospital. Historically, gardens have always been considered a place of healing, and the importance of our natural ecosystems remains relevant to us all, and to the health and happiness of future generations. I feel personally enriched by this experience, and I look forward to seeing the new hospital open in 2022, knowing that the Campbelltown community will share an incredible sense of pride in how safe and inclusive they have made this new welcoming hospital feel.

Thank you to the many people living and working on Dharawal land who participated in the drawing workshops and a special acknowledgement to the Aboriginal people who generously shared their cultural knowledge in the productions of these artworks, Campbelltown Arts Centre, NSW Health and The Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan.

About Erica Seccombe

Erica is a visual artist based in the Canberra region, living in semi-rural New South Wales (NSW) and is a senior lecturer at the School of Art & Design, Australian National University. Erica’s collaborative and interdisciplinary arts practice spans traditional lens-based imaging, print media and drawing, to experimental digital platforms using frontier scientific visualisation software, such as time-resolved (4D) micro-X-ray Computed Tomography through immersive stereoscopic digital projection installations and 3D printing. Erica’s work is held in private and national collections, and notably, her work ‘Metamorphosis’ won the 2018 Waterhouse Natural Science Art prize, and in 2015 her work, ‘Virtual Life’ 2014 won the Inaugural Paramor Prize: Art + Innovation at the Casula Powerhouse Art Centre.