Tom Isaacs’s art centres around concepts of mental illness, mortality and the human condition. In this interview with the Arts Health Network, Tom shares how his art is influenced by his own relationship with mental health.

How did you first come to art practice?

For most of my childhood I thought I would like to be either a medical doctor like my Dad, or perhaps a veterinarian as I loved animals. When I was about sixteen, I found that I wasn’t particularly enjoying studying Chemistry or Biology at school. The subjects that I did enjoy tended to have creative components such as art and creative writing. At that time I was a fairly indifferent student, already struggling with anxiety and depression. I felt I was expected to go to university, but the only option that really appealed to me was art school. Fortunately, my application to Sydney College of the Arts was successful and I went straight from high school to art school. It was during my time as an undergraduate at SCA that I began to make artworks (often performance artworks) that dealt with my experience of depression and interrogated the possible efficacy of art.

What is your own personal relationship between art and health?

I live with depression and anxiety, and my art frequently engages with issues around mental health. At one level this engagement is quite personal; making art is a way to capture something of my experience as a person living with depression and it’s a way to express my desire for relief from suffering. At another level, I am engaged in a public conversation that is broader than my own experience. Through my art practice I hope to challenge the stigma around mental health and to promote thought and discussion about how we view and respond to mental health issues. There is also an ongoing engagement in my work with the proposition that viewing and/or making art can be beneficial for mental health. Although I am ultimately somewhat sceptical about grand claims for the efficacy of art, I have personally found the ongoing practice of making art extremely helpful.

What was it about ritual and performance that drew you to this for your research project?

In 2008, I was in my honours year at SCA researching the topic ‘catharsis in art’. My honours paper opened with summaries of Aristotle’s theory of catharsis from ‘Poetics’ and Sigmund Freud’s theory of abreaction. After that I discussed three groups: artists who made art for their own experience of catharsis; artists who produced work intended to provoke an experience of catharsis in their audiences; and artists who explored spiritual ideas of catharsis.

In the course of my honours research I read ‘Theatres of Human Sacrifice: From Ancient Ritual to Screen Violence’ by Mark Pizatto and I was struck by his comparison of simulated violence on-screen to ritual violence. It led me to ask, what is the relationship between ritual violence and the real violence that takes place in some performance artworks? Could performance art be a form of ritual?

What did you discover about the relationship between ritual, performance and alienation?

There is a long and problematic history of Western performance artists borrowing from the rituals and religious practices of other, so-called primitive, cultures. The racist foundations of these ‘borrowings’ have rightly been criticised and a number of important theorists, including Australian art historian Anne Marsh, have argued that there are important differences between performance art and rituals, at least as ritual is defined in Western anthropological terms. Despite this, some theorists and artists have continued to connect contemporary performance art to ritual and I was interested to explore why.

In my PhD Thesis, I put forward the argument that ‘primitivism’ and ritual have consistently been employed or evoked as a response or solution to the problem of ‘alienation’. My argument was supported by the analysis of a number of movements from the history of performance art and the performative avant-garde, such as Dada, Surrealism, Fluxus, Viennese Actionism, Body Art, and Ritual Art (though I note that different artists and movements seemed to understand alienation differently). Working from the understanding that performance art is not a form of ritual, I explored a number of possible ways that performance art, particularly body art, could address alienation—defined for my purposes in psychoanalytic terms—in a manner different to that achieved through ritual. Using Julia Kristeva’s theory of the ‘subject-in-process’, I argued that body art may make us aware of the problem of alienation, it may provide temporary relief from the experience of alienation, and it may highlight and/or oppose the symptoms of alienated life (such as self-destructive behaviours, sexual violence, and the lure of fascism). Lastly, during the discussion of my own work, I explored the relationship between depression and alienation and I theorised that art could be a creative venue to propose and explore possible solutions to the problems of alienation/depression. In the artworks I produced as part of my PhD I explored three such possible solutions: 1. A return to religion and ritual; 2. The psychoanalytic process; 3. Art-making.

Which of your projects have explored this relationship?

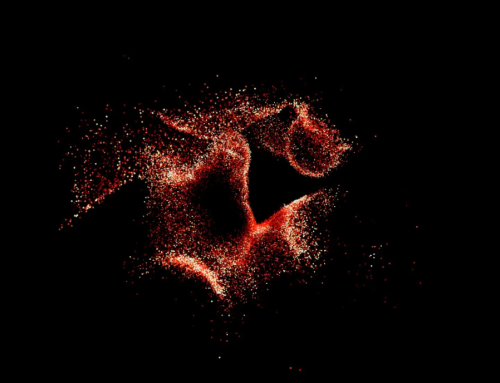

These are stills from a performance titled ‘Night Soil’ (2015-2022), videography by Motel Picture Company. For the performance I lay under a sheet of grey felt in a specially constructed wooden bed while my assistant, Ben, covered my body with soil. I lay under the soil for some time before emerging. ‘Night Soil’ depicts alienation and depression as deathly and highlights the danger that these states represent if left untreated. More hopefully, it also evokes the possibility of healing or resurrection through my emergence at the end of the performance.

‘Night Soil’ by Tom Isaacs

The performance draws from all three of my main interest areas: The work exists in relationship to a history of endurance performance, particularly works using beds (e.g., ‘Bed’ by Chris Burden) or those involving live burial (e.g., ‘Suelo Común’ by Regina Jose Galindo); it also evokes funeral rites and ritual practices involving live burial; and finally, the use of the bed evokes dreams which are of particular interest in the psychoanalytic process.

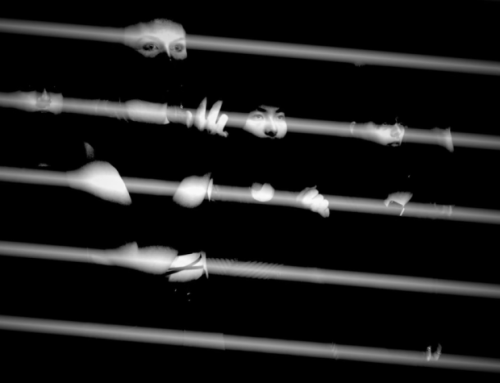

These are stills from documentation of a performance titled ‘Dream Analysis’ (2018), videography by Danica Knezevic. For the performance I slept on a psychiatric couch for two hours. Audience members were invited to take turns sitting in the empty chair at the head of the couch.

These are stills from documentation of a performance titled ‘Dream Analysis’ (2018), videography by Danica Knezevic. For the performance I slept on a psychiatric couch for two hours. Audience members were invited to take turns sitting in the empty chair at the head of the couch.

‘Dream Analysis’ by Tom Issacs.

‘Dream Analysis’ explores ideas of care through participatory performance and the potential efficacy of the psychoanalytic process as a response to alienation and depression. The arrangement of couch and chair echoes the psychoanalytic session and audience members who sit in the chair take the analyst’s position. No ‘interpretations’ are necessary, but the audience member may feel some responsibility to hold space with me so that I am not alone. My slumber during this performance was aided by a moderately large dose of my psychiatric medication at the time which had a quite strong sedative effect.

What outcomes have become evident from your research, specifically around the relationship between artistic expression and dealing with the manifestations of alienation?

Given that my research is speculative and not quantitative, I hesitate to use the word ‘outcomes’. Having said that, through this research I feel that I’ve made a strong case for the position that viewing and making art can disrupt our experience of alienation (albeit temporarily), highlight and challenge the symptoms of alienation, and help us to consider potential solutions to the problem of alienation.

One thought I’ve had since finishing the paper, however, is that while art has the power to move or disturb the viewer, the greater part of its power to address alienation seems to be reserved for the person making the artwork. I’m really interested to continue exploring art making and participatory performance as ongoing practices which may address and even alleviate alienation, depression and suffering.

What do you think (and/or hope) the melding of ritual and performance can achieve, and what needs to be done to support these?

There’s a lot we can learn from ritual and religious practices that could help us to approach some of the problems and deadlocks of our current society and culture, but I don’t necessarily believe that art and ritual can be melded. It’s possible to create ritual-like performances, though it’s important to be careful when drawing from cultures and practices other than one’s own, but these performances are unlikely to function for audiences as a ritual would for a religious community. Even if we don’t seek to employ art as ritual, viewing and making art may help us to escape the pervasive and alienating rationalism and individualism of our society, if only temporarily. Art is also a great space to explore potential solutions to problems like alienation and to speculate about alternative ways of being.

What does the future hold for you as a researcher, artist and person?

Many things I hope! I plan to continue making art and I already have a few art projects in the pipeline: This month I am exhibiting ‘Emergency Blankets’ (three quilts and a live performance) in ‘Carnivale Catastrophe’ curated by Fiona Davies and presented by Modern Art Projects Blue Mountains at Cementa 22, 19-22 May, 2022. https://cementa.com.au/

Next month I am performing my work-in-development ‘Shivah’ in LIVE DREAMS: THRESHOLD curated by Victoria Spence and presented by Performance Space and Carriageworks, 11 June, 2022. https://performancespace.com.au/programs/live-dreams-june-2022/

I’d like to continue my academic and artistic research exploring the possible efficacy of making, viewing, and participating in art as responses to the problems of alienation, depression and suffering. I’d also like to explore teaching at a university level, so that job hunt will start reasonably soon!