This article by Rebecca Vukovic originally appeared in Teacher Magazine.

In these uncertain times, how do teachers support students to make sense of the coronavirus pandemic and give them the tools to navigate the challenges that could come once the disease is under control?

Professor Peter O’Connor from the University of Auckland suggests arts-based approaches to building resilience in students in times of disaster. ‘The world has sort of stumbled from one disaster to another and Australia certainly has — Australia has stumbled from bushfires to floods and now to the Covid-19 virus — and how we make sense of that, and how children make sense of that, and the role of schools in that is vital,’ he says.

O’Connor has a wealth of experience using arts-based methodologies to build resilience in young people to help them overcome trauma following disaster. Throughout his career he has worked in prisons, psychiatric hospitals, earthquake zones and with the homeless using arts-based approaches. He also supported schools through the earthquakes in Christchurch and Mexico City, and more recently the bushfire crisis in Australia.

‘I guess I’ve had quite a bit of experience now in working directly with children and teachers when they return to school after a disaster,’ O’Connor says.

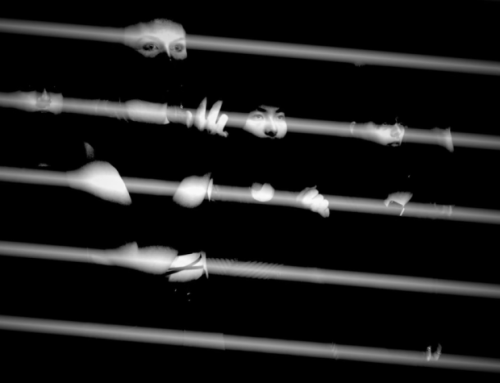

‘I mean, none of us can make sense of Covid-19 but it must be particularly difficult if you’re nine or 10-years-old and you see adults so nervous and scared and unsure, and the world doesn’t seem to have anything holding it together. How you might use the arts to work through that in schools is really important.’

Why an arts-based approach?

O’Connor says the arts are a way of thinking and expressing that really gets to the depth of how we think and feel about what is going on in the world around us.

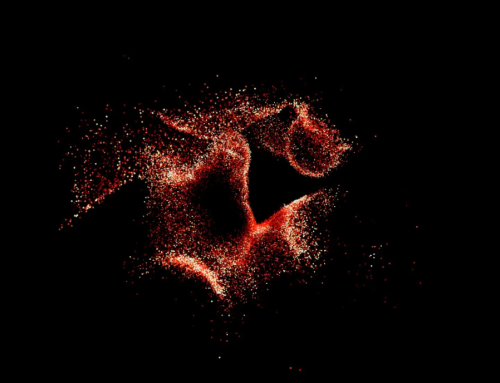

‘I often find with young boys in particular, they find it really difficult to talk about things but sometimes they can do it with their bodies, or they can paint it or they can draw it, or they can dance it,’ he says.

‘Post-disaster, the arts allow people to consider the past and provide an opportunity to mourn and grieve what is lost,’ O’Connor adds.

‘When we need to make sense of what we’ve lost, we often do that in poetry or we do that in a range of different ways, and these are very natural kinds of processes. So the link to the past is really important in schools.

‘Then there’s this capacity for the arts to link us together, which is really tricky in this current crisis where we have to self-isolate.

‘Then finally, the arts remind us of the possibilities of the future because the arts are all about the imagination and one of the things that’s really important post-disaster is that we can imagine that things can get better and that will be really important to us in any crisis, but especially in the current crisis.’

O’Connor says the arts by their very nature provide a safe distance for people to respond to disaster.

‘You don’t need kids coming in and reliving what has happened to them but you do need the arts to help them shape and think and reimagine the way they might be,’ he explains.

O’Connor says it’s critical during this time to give students the opportunity to safely talk about their fears and worries about the world, and give them the chance to engage with their feelings.

Responding to the Australian bushfire crisis

In January, O’Connor was approached by Australian academic colleagues to lead a project to help teachers when students returned to school during the bushfire crisis that devastated communities throughout Australia. He worked alongside his colleague Professor Carol Mutch, who is also the UNESCO Education Commissioner for New Zealand, on this project.

What resulted was a one-day gathering of 30 academic experts from arts, health, education and disaster recovery, from the Universities of Melbourne, Sydney, Central Queensland, New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia.

‘One of the things that we decided really quickly, and I drove that through my own experience, was that we needed to have advice and support for teachers on the first day back. What do you do with all these little ones coming in with stories and fear and worry? How do you work with those stories in a safe way? How do you do it so you’re not re-traumatising them?’ O’Connor says.

They collated research-based, evidence-informed resources which were available online to make them as accessible as possible. They managed to get it all up and running within five days and named it the Banksia Initiative, after the flower native to Australia.

‘The extraordinary thing about the Banksia flower is that it only flowers after extreme heat so the fires, that destruction, causes the seeds to open and what results is extraordinary beauty,’ he says.

The mission of the Banksia Initiative is to provide reliable, research-based advice to schools on how to use the arts post-disaster. The resources on the site can be used with students of all ages, from Kindergarten all the way to senior secondary.

‘It was created for the specific context of bushfires but those resources are available and should guide and help teachers through any disaster and they will be, I’m hoping, used depending on how big the disaster of Covid-19 is and what the dislocation is for communities and children,’ he says.

Supporting teachers through a crisis

O’Connor says the academics were really spurred on to get the Banksia Initiative up and running by the fact that teachers desperately wanted to do the right thing but they were unclear on what they should do post-disaster.

‘There’s a lot of advice on going back to normal, whatever normal means, who knows how does the world go back to normal after Covid-19? I have no idea. Normal will never be the same,’ O’Connor says. ‘Those communities that were devastated by the bushfires, there’s no normal to go back to.’

In January, the Banksia Initiative met in Sydney and provided a practical arts-based workshop for around 50 teachers, and a further 200 by webinar. O’Connor says he was able to gauge how teachers were feeling during these sessions and that gave him a good sense of the resources they needed to support their work in the classroom.

‘I think it was the understanding that they wanted to work in ways that were safe to talk about really difficult subjects so that they didn’t end up with enormous floods of tears, that kids weren’t feeling that they needed to talk about their own personal story,’ he says.

One of the ways they did this was to partner with the Sydney Theatre Company to provide primary schools with large, picture story books.

‘So what we did was we provided resources to teachers around what is a really good picture book? We provide opportunities for kids to talk about things so they aren’t talking about the bushfires but they’ll talk about the things that are connected to the bushfires. So for example, talking about loss, talking about worry, talking about bravery, talking about caring for each other — which is connected to everything that sits under what happened in the bushfires, but isn’t.’

O’Connor says whenever he’s worked in these kinds of situations, teachers often find it difficult to know they’re doing the right thing.

‘Providing them with resources which are the result of years of research and work and study, providing them with the security that yes, actually what we’re suggesting to you is a safe bet. These are the things you can and should do with the children,’ he says.

Structures for staff and students to talk about Covid-19

‘The other thing that really struck me when I was in Sydney was that when I sat with about 25 teachers, I was bowled over by the depth of emotion and feeling that they had about what was happening in Australia … I realised that what’s also really important for schools is that we work with children but we also work with the teachers.’

O’Connor says that once people return to their lives and are out of isolation, we’ll need structures in places by which we’ll be able to talk about Covid-19, and he believes the arts is probably the best way to do so.

‘As schools shut across Australia for a period of time, and when they reopen, it’s important we all reconnect as humans together in classrooms — we’ll need to play a bit, we’ll need to have some fun, we’ll need to laugh together, we’ll need to just be with each other in a way that’s going to be really important after being isolated from each other and how we do that, the role of teachers in doing that, will be enormous,’ he says.

‘We know that children will come back to school, we will have lost grandparents and parents and members of their community, and the community will have suffered in enormous ways, ways maybe that we don’t even understand at this point. Schools are always places of learning but they’re also places where communities heal.’

Think about the ways you support students through times of crisis. What have been some of the most effective ways you’ve managed to have children express their feelings and worries? Are arts-based approaches something you’ve considered?

To find out more about the Banksia Initiative, visit the Resources section of our website.