Alannah Dair is an artist based on unceded Gadigal Land in so called Sydney. Her artistic practice sheds light on issues relating to chronic illness and the social, cultural and medical frameworks that contribute to one’s experience of invisible illness and persistent pain. In an interview with the Arts Health Network, Alannah gives a deeper insight into her artistic practice.

What inspired your interdisciplinary art style and your beginnings as an artist?

From as early as I can remember I have always gravitated to the arts. I consider myself very lucky to have had parents that fostered my creativity from a young age, allowing my brother and I to express ourselves through multiple outlets such as music, dance, film, fine arts, and so on.

But I would say my current artistic practice grew out of my initial start as a painting major at the Queensland College of Art, Griffith University in Brisbane. It was here during my undergraduate degree that I began to shape my understanding of self and what I truly wanted to see from my practice.

Stathis Logothetis, E273, 1980, mixed media, long-term loan of Alpha Bank Collection, Athens, to National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (EMST), installation view, antidoron. The EMST Collection, Fridericanum Kassel, photo: Mathias Völzke, Image from Documenta 14, https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/22278/ stathis-logothetis

A pivotal point in the development of my work came when I visited the 2017 Venice Biennale and Documenta14 as part of a university study tour. After spending a few weeks surrounded by such a vast array of contemporary art, I noticed that I took a particular interest in works that pushed the boundaries of painting, often negotiating an identity somewhere between painting, sculpture, and object. I began questioning the nature of painting; when did painting no longer become painting? Can it be a painting if paint is barely, if at all, present in the object? What can be understood as painting and not-painting? As I contemplated these questions, I came across the work of Greek artist Stathis Logothetis inside the Fridericanum. A work titled E273 seemingly oozed from its frame out into the space of the gallery, blurring the lines between painting, sculpture, and object, acting simultaneously as both a violent and violated body. Even now I get excited thinking about this work and how embodied and alive it felt. It was at that moment that I knew I would explore expanded painting as a lens for my practice.

From this point onwards the theories of expanded painting practice argued by Australian painter Mark Titmarsh became instrumental in the development of my practice. Even now at the halfway point in my Master of Fine Arts degree at the Sydney College of the Arts, expanded painting can be a lens with which to view and access my practice. In adopting this framework of painting in its expanded form, I ultimately gave myself permission to push my practice into ‘not-painting’ to critically analyse what materials were key to creating my work. At this point in time, I’m sitting with my work to understand it, as painting and ‘not-painting’ as sculpture, as installation, as objects.

As for inspirations, I currently find myself inspired by the work of contemporary artists such as Eugenie Lee, Kate Bohunnis, Solomon Kammer, P. Staff, FlucT (a collaborative work by Monica Mirabile and Sigrid Lauren) and duo Pakui Hardware (comprised of Neringa Cerniauskaite and Ugnius Gelguda) to name but a few.

What are some of the different processes behind the work you create?

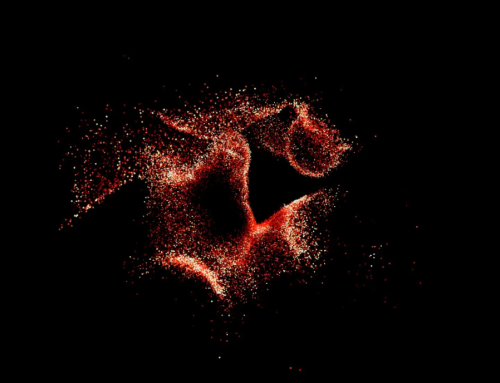

Alannah Dair, experimentation in the studio, 2022, lycra, LED light, surgical scissors, metal hooks. Courtesy of the artist.

I currently create somewhat site-specific installations that require the use of tension to hold taught lycra fabric and medicalised hardware. These materials assume forms that act as object-bodies; manifestations of the experiences I’ve had living with chronic illness.

When installing in a new space I always approach it with an open mind, to learn from it, to see what it brings to my work and what my work can bring to the space depending on the presenting limitations and possibilities. I often position my materials so that they don’t remain fixed, rather as I form my work the medical hardware slides and rotates as the tension forms between the frame and the fabric, creating previously unforeseen outcomes. The result is an encounter between the materials and myself, informed by my ongoing research and my current state of being at that moment in time. I consider each new installation as existing in a ‘state’ within an ongoing continuation of my development of self, not necessarily as individual ‘finished’ works but one work or body in a constant state of becoming.

Of late, I have been trialling applying heat to my materials to illicit a subtle violence acted onto and within the skin of the work. Burning the fabric can be considered both an act of care (removing disease from my body) and an act of resentment for how living with chronic illness has affected my life. I consider this process to be akin to performing self-surgery on a surrogate body; a way to enact the treatments that have been performed on my body. I’m currently questioning how violence can be considered a form of healing and how this might present itself in my work in the future.

How did you come to bringing health and art together?

I was diagnosed with a chronic inflammatory condition known as endometriosis when I was 16 years old. Currently the only way to receive a confirmed diagnosis is through laparoscopic surgery, which I elected to have in my final year of high school in an attempt to determine the cause of my physical pain. This surgery came after years of increasingly bad menstrual pain, gut and intestinal issues, years of trialling medications with horrific side effects and countless visits to general practitioners and specialists who dismissed my symptoms.

Upon starting my Bachelor of Fine Arts at QCA I found myself turning to art as a cathartic way to process the intangible feelings and emotions I was experiencing as I struggled with my health. Towards the end of 2015 and into early 2016 pain eventually consumed my every day. I couldn’t conceive of making art about anything other than the constant and unfaltering pain produced by my body. I lost what it was to feel pleasure in small things. I was on medications to suppress symptoms from other medications, all in an effort to get some relief from the excruciating pain. I existed in a constant state of ‘burn out’, a walking zombie, yet when it came to art it was something that I would pour all of myself into. I would slave over the printing presses until the early hours of the morning. I would watch the sunrise from the studios. It was as if pushing myself to physical exhaustion was a ‘f*ck you’ to my body; a way to regain control, a way to punish my body for making me go through so much suffering. In hindsight, this was a reckless way to take out my frustration. I suppose I was in a period of grief; grieving what I could have been, who I was before the onset of illness, I felt like my body had failed me.

I began to realise over time that the process of creating my work not only served the purpose of being cathartic; as I transferred my intangible feelings and emotions into three dimensional objects, but also acted as a form of documentation; creating awareness and discussion about the invisible nature of illness, the experience of living with endometriosis, and the social, cultural and medical frameworks that govern our bodies.

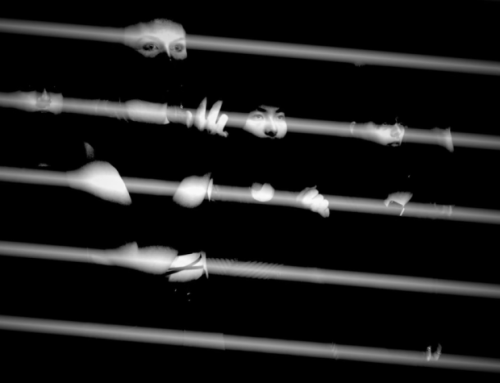

Alannah Dair, Contortion V (no external lighting), 2020, lycra, metal poles, metal clamps, steel wire, safety pins, LED lights. Approximate dimensions: 3m x 2m x 2m. {Dys}Functional, Outer Space. Courtesy of the artist.

For those who don’t know, what is Endometriosis?

Endometriosis, or ‘endo’ for short, is often defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue that grows outside of the uterus in other areas of the body. Endo is often associated with debilitating pelvic pain, fatigue, infertility, pain with intercourse, bowel issues and organ dysfunction among a myriad of other painful symptoms and co-morbidities.

Although endo predominantly affects women and those assigned female at birth, recent research has found several rare cases in cisgender men. This research, along with the discovery of endo in foetuses, girls who have not yet menstruated, and the increasing recognition of extra pelvic endometriosis (disease found outside of the pelvic region) contests the widely used theory of retrograde menstruation as the cause or catalyst for the disease. Despite continual medical debate about the aetiology of endometriosis, treatment options remain tied to supressing menstruation, with neither the theory of origin nor methods of treatment changing that much since the 1920s.

As of July 2021, The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) estimated more than 700,000 Australians are living with endometriosis, with an average diagnosis taking 7 to 12 years from the onset of symptoms.

In your view, how does gender intersect with illness and health?

There’s no denying that gender-based roles and how we are perceived as individuals by the conventions of broader society plays a role in our access to care. Gender, along with socioeconomic, geographic, and cultural factors all intersect when navigating illness and accessing proper healthcare.

It almost goes without saying that women’s bodies have been increasingly pathologised by western biomedical sciences within the last century, rendering normal aspects and functions of their bodies as ‘ill.’ When it comes to conditions such as endometriosis, accessing care can prove difficult due to the normalisation of pain with menstruation, a lack of education and awareness of the disease amongst practitioners, and the continuing notion that women’s pain, without a clear visible source, exists as psychosomatic.

Additionally, due to endo being considered a woman’s disease, transgender, non-binary, gender diverse and intersex individuals with endometriosis face further obstacles in seeking proper care within our current medical system.

Alannah Dair. Close up images of The patient. The doctor. The host. The vessel, 2022, lycra, metal hooks, safety pins, metal poles, metal clamps, steel wire, LED light source, 2.5m x 1.5m x 2.5m. Metro Arts, Brisbane. Images by Carl Warner. Courtesy of the artist.

How do you observe chronic illness in your recent installation titled ‘The patient. The doctor. The host. The vessel.’?

In this work medicalised hardware and material ‘skins’ literally stretch, contract and are held in tension within themselves, as the work negotiates a state of being between health and illness. The lycra fabric can be read as both inscripted surface and internal landscape; acting as both object and subject affected and informed by the frameworks of society, yet also extending and expanding beyond these frameworks out into the space. Considering the chronically ill body as extending beyond the frameworks that wish to contain it, we can observe people with chronic illness not as ‘ill’ but rather living within an ill society.

This work addresses the complex relationship that I have with medicine. Without some form of medical intervention, I wouldn’t be able to have an art practice let alone function on a daily basis. Having said this, over the years I have been prescribed many medications that have caused more harm than good. I’ve also had countless practitioners who have dismissed me, gaslit me and made me feel isolated in my experience with endometriosis as a patient, host and vessel of this chronic illness. These experiences have ultimately forced me to become my own advocate and have required me to play the role of the doctor in deciding the best management of my pain and presenting symptoms.

Alannah Dair. The patient. The doctor. The host. The vessel. Reconfiguration for Pari, 2022, lycra, metal hooks, safety pins, metal poles, metal clamps, steel wire, LED light source, 2.5m x 1.5m x 2m. Pari, Parramatta, NSW. Image by Terence-Kent Ow. Courtesy of the artist.

How do you think contemporary art practice can contribute to our understandings of health?

I believe art can have a range of benefits, but what I’m most currently interested in is how contemporary art practice can expand upon and articulate our understandings of chronic illness as a lived and embodied experience. When one is asked to communicate their experience of pain and/or illness, whether this be to a medical professional, friend or family member, language seemingly falls short. We often revert to using metaphors to describe aspects of pain, but it never quite encapsulates the experience we feel through our lived bodies. Professor Elaine Scarry argues that physical pain not only resists language but actively destroys it. With this in mind, could creative practice potentially bridge this gap in communication between patient and practitioner, connecting and repositioning the chronically ill individual with broader society?

I believe by opening up areas of enquiry that blur the lines between art, social theory, science and morality, new possibilities of becoming other can exist. Imagine an exhibition on chronic illness where doctors, specialists, family members, friends and the general public come to engage in how people experience their bodies in relation to pain and illness? Perhaps this could spark empathy to create change within our current medical system, and change social and cultural attitudes to chronic illness? You’ll have to follow my practice to find out.

Alannah Dair. Close up image of The patient. The doctor. The host. The vessel. Reconfiguration for Pari, 2022, lycra, metal hooks, safety pins, metal poles, metal clamps, steel wire, LED light source, 2.5m x 1.5m x 2m. Pari, Parramatta, NSW. Image by Terence-Kent Ow. Courtesy of the artist.

What do you hope to accomplish through your art?

One of my key aims within my current MFA research is to highlight the gaps within our current medical system and medical education in the hopes that my project can effect change; whether that be by affecting clinicians’ empathy and their role in the wellbeing of the patient through the engagement of creative practice or empowering individuals to take a more active role in their own care.

Alannah Dair, close up of studio experimentation during London residency, 2019, lycra, metal poles, metal clamps, steel wire, safety pins, LED light. Approximate dimensions: 2m x 1.5m x 1.5m. Raw Labs, East London. Courtesy of the artist.

As a person with a chronic illness, I am sharing my experience of health in the hope that it can result in worthwhile discussions and be of benefit to others; creating an overall sense of community and identity.

Although experiences of chronic illness vary significantly for each individual, by adding my own voice to the plethora of voices held by people with chronic illness, I aim to expand upon our collective knowledge of what chronic illness can be; that it is not one fixed ‘thing’ and that the concept of being chronically ill within Western society needs to be rethought – reconfigured – challenged – expanded. This expanded discourse relates to another objective of mine; that is, to raise further questions about the way that society more broadly perceives those who are chronically ill and how those perceptions affect the lives of chronically ill people.

More information regarding Alannah and her upcoming projects can be found on her website https://alannahdair.com/ and Instagram https://www.instagram.com/alannahdair/.