Dr Gaynor Macdonald is a Senior Lecturer and Consultant Anthropologist in the Department of Anthropology, University of Sydney. A social anthropologist with experience of dementia care, she created Dementia Reframed with Dr Jane Mears in 2015. Dementia Reframed aims to change attitudes around dementia and approaches to care, while also carers with information and support. We talked to Gaynor ahead of the Stitch it for Dementia: Carer Craftivist event, a workshop where carers engage in ‘gentle protest’ through stitching, using their artworks to seek a better world for people impacted by dementia.

Tell me about how Dementia Reframed came about.

In 2015, I was looking after my husband, who had Alzheimer’s with a bit of vascular dementia, and I was appalled at the complete lack of support and information – of the right kind – for carers. And I was appalled to find out how unbelievably stressed and depressed carers of people with dementia are.

Even though a huge amount of noise is made about residential aged care – partly because it can be appalling – around 70% of people living with dementia are in their own homes. And that’s where the real support is needed. The two kinds of support that are generally offered to people are counselling and respite. The idea of counselling used to annoy me intensely when I was caring. I wasn’t a mess, I didn’t want counselling. I wanted really practical information.

With dementia, there are very, very specific demands upon carers – which the more generic notion of being a carer doesn’t quite get to. The person with dementia is continually changing and therefore you, as a carer, have to change. A person with dementia wants to communicate, and so you have to learn how to communicate with them.

When it comes to dementia, you’re not even told that you need to adjust and change. You’re not told why somebody you love and have known for the last 50 years is suddenly swearing at you or doesn’t like chocolate cake anymore.

And there are quite easy ways to know why. That might sound like an outrageous thing for me to say, but there are, and we’re not telling people. So that’s my job.

Since then, I’ve received training in the Positive Approach to Care, a fabulous American program designed by a woman called Teepa Snow. I’m now a Positive Approach to Care independent trainer and consultant myself because I love that program. I didn’t know about it when I was looking after my husband, Charlie, but it has all the values and approaches that we started off with in Dementia Reframed.

When you talk about ‘reframing’ dementia, what is it you would like to achieve?

I show everyone this picture of my husband, Charlie, with his lovely big smile. The point of that picture is that it was taken six weeks before he died. He was very advanced in his dementia at that stage. He wasn’t mobile. He couldn’t eat, he couldn’t speak, he couldn’t have a conversation with us, but we could still engage with him and he could still smile. And that’s the image I would like everybody to have of advanced dementia, rather than this awful, passive, sitting in a great big chair in a nursing home. Vacantly staring into space. Now that doesn’t mean that Charlie didn’t vacantly stare in his space, but he didn’t do it all the time.

‘Reframing’ dementia is about learning how to engage people whose communicative capacities are changing or diminishing. I often like to call dementia a disease of communication. The treatment is communication, and good communication skills, but you need a certain kind of information in order to be able to do that. It isn’t guesswork. There’s an awful lot of people can learn.

So, Dementia Reframed does three key things. We do a lot of research and give talks to help change attitudes to dementia. To get rid of the doom and gloom and the negative reactions – because they’re not helpful. They make care much, much harder. People don’t want to talk about it, and so they back off, or they don’t come visit, and you end up really isolated.

The second thing we do is workshops and information sessions and carer story days, for actual carers. We do that through what we call Charlie’s Place. And then the third thing that we do is run a website for carers, designed by people with experience in dementia care. We’re not interested in their qualifications in any other context. Their major qualification is that they have lived experience of caring for someone dementia, because if you haven’t, you just don’t get it.

The role of the dementia carer is not the conventional patient-carer model. It has to be interpreted as a partnership. A person with dementia is going to become more vulnerable. They’re going to be more dependent on the people around them. At any point in time the person with dementia should be enveloped in a really positive, affirming relationship.

Our workshops, for instance, help people understand what it means to be in relationship with somebody who’s changing. A really helpful thing with dementia is simply knowing what’s going to happen next, so that you’re not continually being confronted and exasperated by what’s happening.

What kind of implications does this ‘relationship’ model of dementia have?

I think relationships between people with dementia and their carers act as a kind of benchmark for true compassion. Understanding that relationship, and learning how to support someone through that relationship – if we could all do that, we would actually have a transformed social world. We are not just ‘human beings’. We are human social beings. To be human is to be social. I think one of our greatest enemies is this wonderfully economically valuable idea that we’re individuals.

The notion of the partnership I’ve talked about in relation to dementia should apply to any relationship. Including the medical relationship. I’ve been fortunate to have a GP who is fantastic. But I’ve also been to doctors who just expect me to listen and do what I’m told, without acknowledging that I know my husband better than they do, that I spend more time with him, observing his behaviors, his reaction to medications.

It’s easy for the partner in the carer relationship to get sidelined. I was very fortunate. I don’t regard myself as a typical carer at all. I was younger than my husband. I had health and strength. I had a job where I could negotiate my hours – that helped enormously. But I’m also a researcher, I knew how to find the information that I wanted. My father was a medical doctor, and when I got my PhD I would always say to him, ‘Now I’m a real doctor too.’ It was a joke between us. That history means I don’t cringe in front of doctors. Whereas a lot of people do. Even people in the health professions themselves don’t know how to speak back to this medical power. And that has to change.

How would you like to see dementia research change and become more inclusive of the carer’s perspective?

In the process of developing Dementia Reframed, I had access to enormous amounts of information. Including all the useless information they were churning out to carers. There are maybe thousands of studies out there about what’s called the ‘carer burden.’ I couldn’t tell you how many. But personally, I don’t want to know how depressed you think I’m going to get. I want to know how to cope with the next 24 hours.

The whole way that research is being done needs to change. A lot of research is still starting from the researcher perspective. We have to reframe that and start very much from the ground up, from what people with lived experiences are telling us. Researchers might set up nice little consultative committees with carers, but the carers are not driving the research. They’re simply lay people somehow expected to legitimize it.

I’m an anthropologist. I absolutely believe in qualitative research. That doesn’t mean I’m going to throw the quantitative stuff out, but just because you can’t quantify it doesn’t mean it’s not incredibly valuable. These studies need to be about real people living real lives. How you respond to dementia will be determined by your life experience, your cultural domain, your gender, etc.

What about the Stitch It for Dementia: Carer Craftivists event? Do you want to talk about the genesis of that?

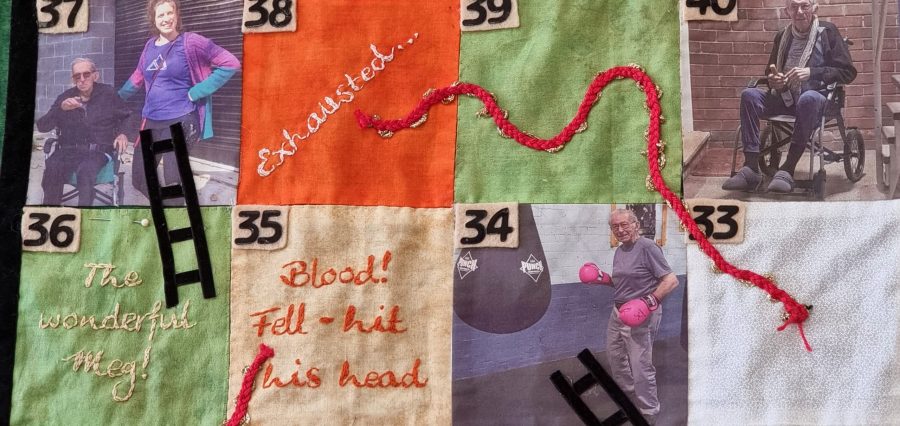

The idea didn’t come from us, it came from Chloe Watfern at SPHERE. But I was really interested in the whole notion of craftivism, of activism through craft. She inspired me, and I started doing a bit of stitching, and then joined the dementia carer group Chloe set up. I stitched a ‘snakes and ladders’ game – ‘The Ups and Downs of Dementia: Often a challenge, never a tragedy’. I used photos of my husband, family and care partners, going from the time we got the diagnosis to the time he died. There are a lot of ladders, but there are also an awful lot of snakes. It includes my experiences such as, ‘Aged “care” was a cruel joke’, and ‘A Carer Gateway to nowhere.’

The Craftivism task was to express the experience of care. I didn’t want to romanticize it. I could talk about some absolutely wonderful times we had, and talk about all things I learned, but there were also times when it was really grim. And so, I thought, how can I symbolize these ups and downs? It’s been a nightmare, to make it work. I’m not a patchwork stitcher, I usually do tapestry or cross-stich – and one thing I’ve learnt through this is that I will never, ever do patchwork again. But it’s been incredibly affirming to spend time with people who’ve been there, who get it. To share this experience with them.

There’s an extraordinary kind of relationship between people who’ve been there. I learned an enormous amount from other people’s stories when I was caring. We’ve all got imaginative, creative capacities, which means that giving people advice is not necessarily the way to go. Helping people to think of their own solutions for their own context is much more constructive. It could be really oppressive when people gave me advice, generic medical advice in particular – I felt like I was expected to be this perfect care person and that is not possible for anyone.

I think that’s the value of things like the Carer Craftivists event, as well as our carer workshops and story times through our project ‘Charlie’s Place’. We’ve had incredibly positive responses to our workshops. We are helping to change attitudes. It’s not about big numbers or anything like that. It’s just a quiet little revolution in attitudes and approaches to care.