Socially engaged artist Vic McEwan from the Cadfactory has just opened a new Exhibition of artworks at the Wagga Wagga Art Gallery. The Exhibition, ‘Face to Face: The new normal’ will be launched on February 19.

‘Face to Face’ is an Exhibition of artworks created by Vic McEwan in collaboration with staff and patients at the Sydney Facial Nerve Clinic. Here McEwan has been undertaking PhD studies on the nature and impact of socially engaged arts practice. Specifically, his work explores new understandings of patient experience, and practices of care we can gain as a result of embedding a contemporary artist in a clinical setting. The artworks form part of the outcomes of his PhD.

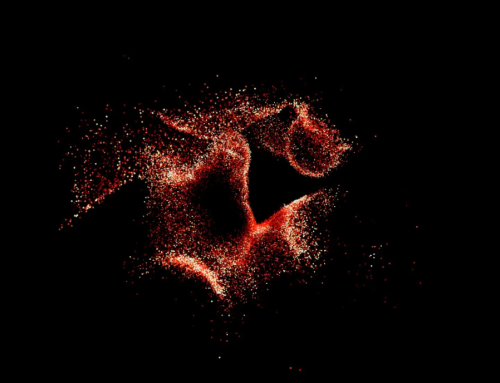

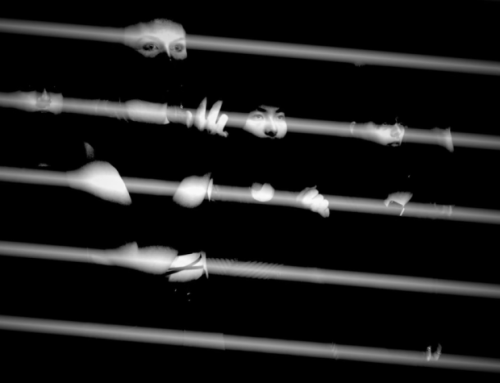

Hand Projections from ‘Face to Face: The new normal’, supplied

McEwan’s PhD approaches the question of how and why the creative arts can be so transformative in a health setting, from the perspective and process of an artist. The Exhibition as a whole, and McEwan’s research, takes a more process, ethics and philosophy oriented approach to the question of understanding ‘impact’.

The works in the Exhibition also explore our relationships with our own and each other’s faces. The Sydney Facial Nerve Clinic is a unique inter-professional health service that enables patients with complex facial nerve impairments to be seen and treated by a team that includes doctors, surgeons, a physiotherapist, other allied health-works (and now, an artist). Impairments to facial nerves can result in people being unable to feel or use the muscles in their face, preventing physical expressions of emotion such as smiling, creating difficulties in speech or eating, or losing muscle tone. Patients face extensive social challenges as a result of these impairments.

In former years, ‘Face to Face’ might have been considered as part of the ‘Medical Humanities’ – works that help doctors understand and better empathise with patient experience. But bringing a contemporary arts practices into the clinic has enabled more than this – the disrupting or resisting of medical authority; the assertion of voice and autonomy in the highly governed spaces of hospitals and care institutions (Bolaki, 2016), and the bringing of the social conditions of ill health – or in this case, of navigating the world with a facial difference – into view.

Hand Projections from ‘Face to Face: The new normal’, supplied

In fact, the creative arts have enabled the Medical Humanities to grow more critical – in the best senses of that term. First, of course, we now know deeply and extensively, that the creative arts are critical for our health. Second, arts help us remain critical of the traditional hierarchies and power relations of medicine. Respecting the expertise of those formerly positioned as subordinate to doctors – nurses, allied health (e.g. physio and occupational therapists, social workers and psychologists), not to mention patients and carers – has fuelled a broader and more inclusive international Health Humanities (Crawford et al., 2020). Third, researchers in the Health Humanities and Arts and Health are thinking more critically – that is, beyond and outside former norms and assumptions. New ideas and concepts are opening up for exploration – for example, the idea that aesthetics might themselves be a form of ethics (Macneill, 2014). Or that doctors and other clinicians have bodies too. They are vulnerable, have rich, delicate and ethically complex emotional lives as core components of their professionalism, and suffer and need care, and attending to this is actually a crucial part of being able to offer empathy and compassion to patients. These themes are the stuff of ‘Face to Face’.

During the research process of which the artworks are both part and product, McEwan found that the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas has great relevance for understanding the impacts of socially engaged arts practice. Levinas theorised that the basis of human morality – and of freedom – lies in coming ‘face to face’ (Levinas’s words) with the Other. In this basic face-to-face encounter, the Self recognises simultaneously the Other’s closeness and their distance, and experiences the primary demand to respond ethically – that is, to be responsible – to the Other:

Facial Nerve Harp from ‘Face to Face: The new normal’, supplied

‘The being that expresses itself imposes itself but does so precisely by appealing to me with its destitution and nudity – its hunger – without my being able to be dead to that appeal. Thus in expression the being that imposes itself does not limit, but promotes my freedom, by arousing goodness.’

The collection of works in ‘Face to Face’ is an exemplification of how this ‘freedom’, resulting from the arousal of goodness, might feel. Among other things, the works in ‘Face to Face’ respond to clinicians, connecting with their own bodies and vulnerabilities, as well as with our own, as the audience. McEwan’s research explores how the ethical integrity of the relationship between the artist and his collaborator-‘subjects’ underpins the emergence of the artworks themselves. In turn, the aesthetic integrity of the art creation process is what nourishes and sustains the relationship.

If ‘Face to Face’ asks its audience why they should care about people who suffer from damage or dysfunction to the facial nerve, it answers by touching us, emotionally and, if the audience wishes, physically also. Its impact lies in the ethical qualities with which we respond to the artworks. Those who attend may find their understanding of both facial difference and of socially engaged arts practice immeasurably – and I mean that – deepened.

Vic McEwan, image supplied

The new Exhibition, ‘Face to Face: The new normal’, by artist Vic McEwan will be launched on February 19 at the Wagga Wagga Art Gallery.

References

Bolaki, S. 2016. Illness as Many Narratives : Arts, Medicine and Culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Crawford, P., Brown, B. & Charise, A. (eds). 2020. The Routledge Companion to Health Humanities. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge.

Kuppers, P. 2007. The Scar of Visibility: Medical Performances and Contemporary Art. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Macneill, P. (ed). 2014. Ethics and the Arts. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.