Joselo Ortiz exists within a blurred border between art and medicine. Culture, politics, health, history, and disease all link together in the physical outputs of his artistic practice. He sheds some light on his personal process in an interview with Rosa Clifford.

Your work involves this interdisciplinary collaboration between both your background in health and in art. What inspired your beginning in your career in health and what inspired you to translate your experiences into art?

When I was doing my medical degree in Mexico, I was rotating in different areas of medicine, including gynaecology. Gynaecology was particularly important because we were seeing women in their early 20s with cervical cancer, many of those even sharing the same sexual partner. I was interested, first of all, by the fact that such young women were affected by this cancer, which originates from a sexually transmitted infection, the human papillomavirus. It was interesting that the cancer came from an infection. The relationship it had with sexuality was also very interesting to me as, in a sense, you could see relationships through a microscope, how a virus enters the body and how it is related to the body based on intimate relationships, in a sense the personal becomes public.

I was also surprised to see that in my country only girls were being vaccinated but boys were not. It was kind of a political point, where the public health sector would say ‘okay, well, we will vaccinate women because they are the ones who develop the disease, the cancer’, but boys were being allowed to transmit the virus, they were allowed to be vectors based on this premise from the public health authorities. So, this also intrigued me, how you can read social and political views of a country, depending on the diseases that its population develops. It is kind of seeing the society through the diseases, through a biological point of view. Then, I started studying the virus and how it relates to humans on different levels today.

Could you describe the aspects that drew your interest specifically towards sexual health and sexually transmitted diseases?

I think the aspects that I’m attracted to in medicine might be in other places too, but it is more obvious when we are talking about sexual health. Sexual health directly implicates the symbols of sexuality and the role of sexuality and genitalia. So basically, public health laws are directly affecting our reproductive rights, the way you appear physically, the options you have to access treatment or not. It lies in the core of sexuality, gender and human rights. These aspects seemed clear to me. I also thought it was very interesting to see that this virus, which is invisible to the naked eye, is hosted in reproductive organs, it is embroidered in our history. The human papillomavirus has been with the human race since the early years of our evolution, so these sexual roles and relationships that allow the virus to transmit between one person and another are very ancient, they are primitive and in the core of our existence.

The art you create is so beautiful to look at, but the meaning behind it is more sinister, could you elaborate on this?

Yeah, one style that my art takes is that it’s actually very easy to look at, while many people find it challenging to approach the disease or talk about it. These beautiful and sometimes geometrical shapes, allow people to get a closer look of something they avoid. When the disease is there, nobody wants to get close to it or to look at it, even within the medical profession, many of these themes are not very well spoken about, and many people avoid the themes of sexual health too. But in in this case, the aesthetic of this art allows people to understand the story/infection from a completely different perspective.

Do you feel that the meaning of your art should be left up to interpretation of the viewer?

Of course, I expose the participants in the context, and what the context might tell you depends on your own lived experience, but it will always respond to current sociopolitical conditions. It’s a way of creating this little sphere of history, so when people are looking back at it in the future, they can understand what it was like to live at the same time as us and what our problematics would have been. In a sense, this story is not being written by a particular person, it’s an interpretation of the host-agent relationship between microorganisms in this case, and humans.

What are some of the different processes behind the art you create?

Well, for example, one of my pieces comes from a biopsy that we had taken from a patient. While analysing it through the microscope, I thought about replicating what the skin changes looked like, as if it was a landscape. Another piece is the virus itself, how it looks under a very powerful microscope, and giving it more dimensions using a 3D render. Then, I printed the model and created matrices to transform it in ceramic at different sizes. The whole process was very meaningful, because for the ceramic to be completed it needs to undergo extreme temperatures, which is similar to the treatments that women go through when having a cancer treatment because of an infection on their reproductive organs. It resembles the process that a patient also needs to go through.

A lot of people also don’t know what the virus looks like. As a patient you’re told that you have the human papillomavirus, then you just see perhaps some drawings on the internet, about how the viral spheres look. Having a 3D model of the virus that is causing all this pain to your body is completely revolutionary for the mind. I think that it also works because people don’t know what exactly is evolving and growing in their bodies and which is consuming them. It affects a person on so many levels. Physically, it causes deformities through genital warts, or through cancer. As experienced by many women, it also involves the complete destruction of their sexual lives. In many countries, women are shamed because of this infection, many of them lose all the money they have trying to pay for the treatments. They become unemployed because they have to be resting and going to the hospital all the time. The emotional pain of knowing that perhaps an intimate partner gave you this, makes you realise that the virus is able to hide in an act of love and intimacy. All of that is at times overwhelming, and I think concentrating all that in an image can be powerful in an artistic sense and therapeutic too.

Do you feel that your art making process also influences the way you interact with patients, and your career within health?

Definitely, it allows me to be more empathetic towards patients and to better understand the impact on their lives. It shortens the distance between a doctor, the patient, and your own sense of being human. It definitely raises a lot of values, and I also think, in terms of doctors, it nurtures their understanding of the treatments which they prescribe and the areas that we need to work at to make the treatments more effective, the access easier and the recovery smoother. I think there are a lot of strategies that medicine can learn from art and I’m also trying to practice medicine through art . As Joseph Beuys said, “Art expands its frontiers to territories which didn’t belong to it.” In my practice, I want to practice preventive medicine through art. Imagine people going to an exhibition and understand a whole medical issue without needing to read a 900 page book. In this sense, art also shortens the distance between let’s say preventive medicine and the society. It’s a new way to get people closer to health, and to be critics of the policies in which they participate.

In your experience, do you think there is a place for the collaboration between art and health in healthcare settings?

Definitely, there are already plenty of artists that use art as a therapy, and as another tool for people to understand their own story. I think in my case, I am more inclined to see the human body as a register, I see it as the footprints of the place that it happens to be born, live and die. Hopefully there will be more artists that might go down this path. In my practice, I explore the relationships between the agents and us as hosts. The register that you can see in the form of a disease, also speaks about the physical and social body. It is not only about telling the personal experience, but also telling the context it is in, and then people can identify with certain aspects of it, at different levels. It might be, that some people reflect in a way that some others don’t. I think that is the most valuable thing, that they can read the artwork in a universal language, but the significance of it is very personal. It is kind of gravitating between the public and the personal in a language that everybody can identify with, as a doctor, as a patient, as a politician, as a lawmaker, as the family member of somebody who was affected, as the person who is transmitting it. There’s a resource for all those roles in the artwork.

Are there other factors within your experience of Australian culture or your personal upbringing, that you also represent within your art?

My observations change depending on the culture I am in at the moment. In Mexico, I was very concerned with the vaccination schemes where women were being vaccinated but men were not, which is perhaps as in most countries of the world. It was different in Australia; I was interested in contraception and how contraceptives are managed by regulators. For example, in Mexico, if a woman wants to get contraception, she just needs to go to the pharmacy and is available over the counter. Here, the regulation is very different, you need to go for a consultation and get a prescription. That difference kind of sparked something in me, I was like, ‘what is happening here?’, you know?

Each country has its different policies that perhaps need to be looked at, it varies everywhere. In Australia, the rates of cervical cancer have dropped dramatically after the introduction of vaccination for both women and men, girls and boys. At the beginning, they only vaccinated girls, but then there was a strong advocacy for the vaccination of boys as well, so that entered a few years later and now they are looking at the amazing results in terms of public health. In Australia, women are being screened for the human papillomavirus itself while in most parts of the world that is not the case. In most countries women are asked to sit back, you know, in a vulnerable and uncomfortable position to then have a speculum placed inside and then somebody taking a sample, whereas in here you can do a vaginal swab yourself.

I guess in a way it responds to women taking control of their own bodies in that screening method. I’m not sure yet if it is at this at the same level in terms of access to contraception, it’s just the questions that remain unanswered for the moment, but they are very interesting to look at.

What do you hope to accomplish through your art?

I’d like to raise awareness of how our political views around diseases and health in general can affect millions of people. Another objective is to practice medicine through art and encourage other people to do it, to try to approach medical themes that seem very difficult to talk about. As for the human papillomavirus project, to prevent people from dying of cancer and become critical of the fact that boys are not getting vaccinated, especially in low- and middle-income countries. I would also like to encourage equality in the policies to protect both women and men.

Some of Joselo’s artworks:

18 (Virus), 2016.

HPV Project

Glazed ceramic

17 x 17 x 17 cm / 6.7 in

Image supplied

Three-dimensional model of the virus in glazed ceramic. There are over 100 serotypes of human papillomavirus with the same capsid structure. Serotype 16 is the most prevalent in cervical cancer. Serotype 18 is one of the deadliest along with the 45. Although HPV has many faces, some are more oncogenic than others.

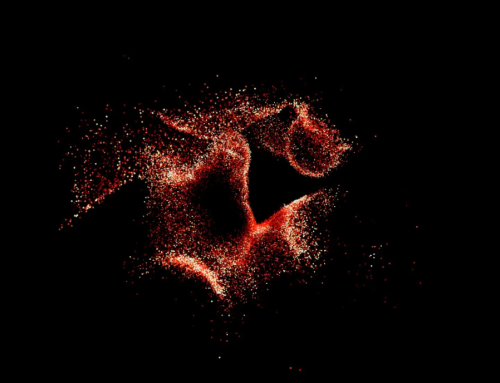

Untitled (Engagement Ring). Image supplied.

The fate and the mark that the virus leaves behind in relationships transcends all levels. It is not something that affects only individually, but interpersonally. The virus affects the trust, love, honesty, respect and security that form a commitment. In addition to deforming a person’s physical image over time, it also has the potential to produce cancer in a large number of human beings. Cervical cancer is caused by this virus transmitted by sexual contact, positioning itself as the second leading cause of cancer death in women in most of low and middle income countries.

Untitled (Pendulum), 2016.

HPV Project

Statistics, Randomness and death

Polyester resin virus, chrome steel base, magnets and 14k white gold chain

Image supplied

Untitled (Pendulum, 2016) is a piece that through game, movement and randomness reveals behaviours and scenarios related with the permanence and impact of HPV in our society.

The chain symbolises the set of political, social, cultural and economic factors that are intertwined, allowing the transmission and integration of HPV in humanity. The virus may seem harmless, small and weightless. However, it’s impact is hard, heavy and lethal. That is why the structure is made of chromed metal, which also provides the ability to reflect ourselves in our approach to observe in detail.

A mix between transparency and black colour gives visibility to this virus that consumes lives, self-esteem, families, hopes and destinies. In order to move, the virus needs someone to throw it, like the impulse that accompanies a sexual behaviour. It is like a game in which we participate when we are not conscious.

Finally, the virus chooses one out of ten infected people to stay, persist and in many cases progress to cancer.

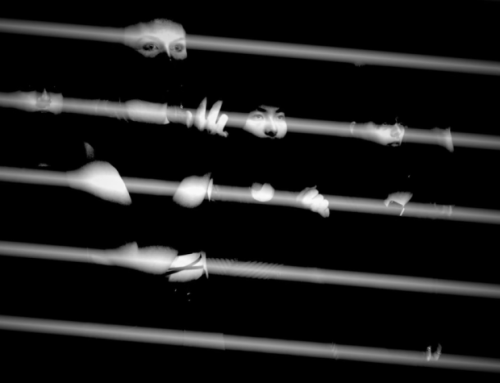

Joselo Ortiz. Image supplied.

Joselo recently collaborated with the Waiting Room Project in an exhibition, ‘Human Papillomavirus: Virus Meets the Skin’ Solo Exhibition. More information on upcoming projects can be found on Joselo’s Instagram @ joseloortizprojects.

Feature image:

18 (Virus), 2016.

HPV Project

Glazed ceramic

17 x 17 x 17 cm / 6.7 in

Image supplied

Article and post by Rosa Clifford