This is an extract from an interview with Professor and Theatre practitioner Peter O’Connor, Head of School, Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education & Social Work, University of Auckland, N.Z.

After making award-winning theatre with Auckland’s homeless, Peter O’Connor was invited by a member of the Los Angeles Skid Row Housing Trust to work with the homeless on LA’s Skid Row. Both he and the Trust knew he one week in his 2019 schedule to initiate, create and complete the project.

Because of the time pressure, Peter requested to work with existing arts organisations and their members. He knew he needed to work with people, who from the outset saw themselves as artists. And this influenced both the content and its execution.

The Los Angeles Poverty Department, Peter emphasises, has done a brilliant job in nurturing diverse arts groups over a long period of time. His 25 participants came from ensembles that focused on music, improvisational drama, photography, creative writing and poetry – skills that hinted at the richness of the kinds of tools for self-expression available as a resource. Before Peter’s intervention, none of these organisations had ever worked together.

By the time Peter arrived in Los Angeles, the Museum of Contemporary Art, one of the most important culture houses in the city, was on board as a performance venue. Other organisations ensured that the participants would be paid for a three-day rehearsal period and the performance on the fourth. From the beginning, their artistry and thus their contribution was honoured.

With his wide experience of theatre-making in prisons and on sites of crisis and chaos with the marginalised, the traumatised and the disenfranchised, Peter fully recognises the importance of theatre in collapsing the binary between “us”, the audience, and “them”, the performers. We hear, see and feel for each other and instilling this empathy creates receptivity. For Peter, theatre embodies the concept that the purpose of all living is for us to become more human. But to make theatre that can do this is always challenging. “How do you create a space, where something shifts?” asks Peter. “How do you shape a work, where something beautiful happens as well as something disruptive? How do you create something in that space that wasn’t there before?”

Struck by the inequality of Skid Row, “a wasteland surrounded by people driving Lamborghinis,” Peter chose to locate tiny scenes from Skid Row that resonated with shared humanity. Inequality was already abundant.

Peter recognised that, “What the people we were working with wanted to make was powerful, disruptive, challenging theatre that wasn’t about telling their own personal stories. Certainly not the stories of how or why they ended up on the street. But stories that spoke to more human concerns.”

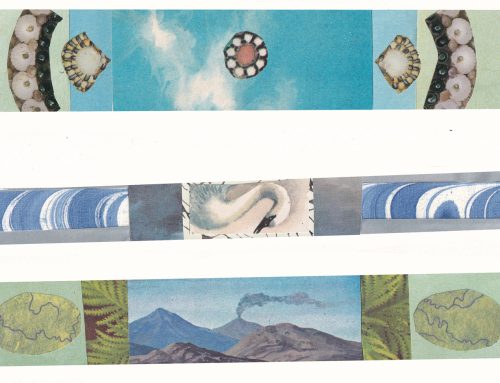

Peter began the first session seeking to find relationship, family and connection through death. Skid Row is a place where a thousand people a year die, three a day. Death is omnipresent. Through this initial dialogue, powerful motifs surfaced to create connection: death, transition, survival, hope; motifs around which to build gallery installations or scenes, tiny thirty second pieces of really powerful theatre.

“Thirty seconds,” says Peter, “is about all you can do. But if you have seven of those looped and you have a beginning and you have a way of bringing everybody together at the end, with actors repeating their scenes multiple times, you have a 45 minute show.” Peter suggests that the scenes that were developed over the three days were both powerful and yet, for Skid Row, ordinary: “people being born, people being killed, people having arguments, people imagining they could fly.” However, the link between all the installations was gun violence and motherhood. Peter reflects on the participants’ experiences, “we know that black men are shot by the police in Los Angeles and across the United States in alarming numbers. One more day of rehearsal”, says Peter, “would have made that (through the grieving mothers) clearer and cleaner.”

There was no fixed order for the audience, they moved between the installations and the way the narrative developed depended on each audience member’s path. In order to hear each scene, the audience had to step in very close to the actors: “you had to be that close to see and to hear and to feel. And that’s what I wanted. The audience had to be right inside the cacophony of Skid Row.”

Peter hopes that some of the content was so deeply disturbing for the audience, particularly the white audience, that their wellbeing might shift. “Perhaps they may no longer find the homeless invisible.” For the cast, Peer recognises that a three-day theatre project isn’t going to change anyone’s lives. Peter concludes, “But in those extraordinary pieces we changed everything. In that moment, we weren’t homeless people or academics from Auckland, we were just theatre-makers. So, what did we achieve? We achieved a beautiful piece of theatre. It’s fucking gorgeous.” Peter laughs, “I think that’s an academic term, ‘fucking gorgeous’.”

Peter returns to Los Angeles and to skid Row in 2020 for another show with slightly more time to devise it. Because continuity is important, family is important, and that’s what Peter recognises they have become, a family of artists. “As artists,” says Peter, “We make. Whatever we do, we make.”