Dancer, choreographer and writer Mathew Bergan is the founder of Dancing Warrior Yoga school in Sydney, who now runs Sound Healing Workshops.

In a recent seminar run by the Australian Dance Theatre’s International Centre for Choreography, Mathew was one of five artists invited to speak on ‘Queer Performance as Resistance’.

Mathew talked with Arts Health Network’s Ian Thomson about resilience, the transformative power of performance, and how the short film ‘Resonance (1991)’ used dance as a form of protest against the attitudes of the times.

The full short film ‘Resonance’ can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1cb7Oe1zoE

“Dance allows a poetic space for people to be present to something that perhaps they don’t yet understand” – Mathew Bergan

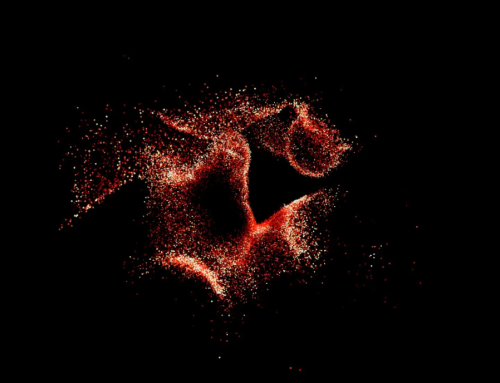

Still from the film ‘Resonance’ (1991), supplied

How did the film ‘Resonance’ come about, and why is it so often seen as a milestone of the arts as a form of queer resistance?

‘Resonance’ was 12 minutes of beautiful Film Noir made by Simon Hunt and the late Stephen Cummins, who were teaching film and sound respectively at the College of Fine Arts (COFA) in Sydney. Together they wrote a script that tapped into the Zeitgeist about the gay bashings, hate crimes, panic and the HIV/AIDS epidemic happening at the time. ‘Resonance’ became a film that explored those complex narratives through physical gesture and dance.

At the time the film was made, I was working with Chad Courtney on dance projects exploring notions of masculinity especially toxic masculinity, particularly within the context of heteronormative Australian sporting culture, which could be a dangerous place for a queer person at that time. We were using dance to express a physical narrative around issues like dominance and surrender, public and private, acceptance and rejection.

Stephen and Simon had written a series of short poems within the film exploring masculinity, homophobia and misogyny; but also intimacy, love and optimism. We wanted to find a way to express beauty in a time that was dark and brutal, where a lot of gay men were dying of AIDS, or being bashed or even murdered for simply been queer. Gay bashing, aptly called hate crimes today, had become a sport among young heterosexual men visiting Oxford Street in Sydney. During this time the media often portrayed gay men as sick, diseased and contagious – which promoted fear and loathing. At the time, our lives didn’t feel safe in the hands of the police. They did nothing about it. There was no police liaison with the queer community like we have now.

On the flip side, it was a ripe time for queer art-making. We had a lot of comment to make and there was a real intensity to our storytelling. There was an urgency to artistic expression because of the AIDS pandemic. Queer people often felt it was a race against a death sentence, and as Act Up’s protestation declared: Silence = Death.

Time was of the essence and there was a drive to make things happen, without the concern for contemporary manifestations of political correctness and cancel-culture.

What role did you feel dance itself could play in creating change?

Art reflects culture. We had the passion, drive, urgency and technology to do this at that time. It was an intense environment. There was an urgency to life. Stories had to be told. We were unapologetic in our rage. It was our time to reflect and dissect the discrimination we lived with on a daily basis.

The beauty of dance is that it’s open to interpretation and gives people permission to create their own experience. Dance performance can range from gesture, physical theatre to contemporary and/or classic interpretations. Dance can be raw. There is not always a need to conceptualise it. Dance allows a poetic space for people to be present to something that perhaps they don’t yet understand.

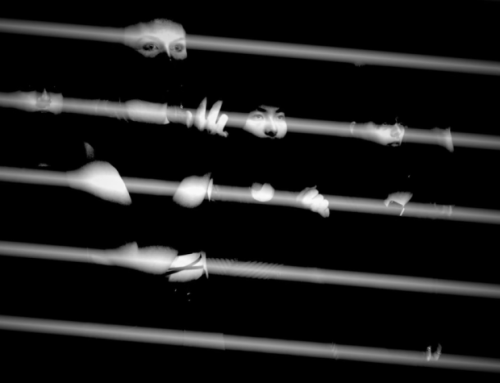

There is a beauty in two men dancing and showing intimacy to one and other, but there can also be brutality and violence, so we danced that fine line. If the project had been a play rather than a dance performance, it would have been a completely different experience, more driven by words and fervour. Each art form has an intrinsic and unique ability to tell a story in a certain way. Our physical stories were terrifyingly beautiful, sensual, uncomfortable and emotive.

Still from the film ‘Resonance’ (1991), supplied

What did you want to achieve?

When ‘Resonance’ was released, it took off. We could never have predicted its success. It tapped into the global spirit of the times. Since then, it toured the world on the queer festival circuit, and now appears in libraries, university archives and seminars on queer social and cinema studies.

The film got a message out to the world that the times we were living in were urgent, brutal and dysfunctional, but at the same time could be beautiful. It was a potent collaboration of artists who were at their pinnacle. The project was bigger than any one of us. Even on set while filming, there was a sort of electricity in the air and a sense that this film was going to go places. You could feel it. Everyone went above and beyond, as there had never really been a short film like it. Simon Hunt’s compelling music score gave the film its magic and really lifted the choreography to a whole new level.

In 1991, we opened the Sydney Film Festival short film program as a queer film, won the audience award and were featured on the front page of the Herald METRO. It achieved a lot more than any of us intended. Remember in 1991, seeing two men kissing sensually on screen was a rebellious act. We provocatively used this to leverage our publicity. We wanted recognition that our love is worthy.

Performance often has the potential to speak to a larger audience, amplify a message and experience. How did you leverage this in 1990s?

As a queer person surviving in those times, I was moved by groups like Act-Up for their unapologetic interventions at global medical conventions with group lie-ins and disruption. (Act-Up, AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power is an international, grassroots political group working to end the AIDS pandemic. The group set out to improve the lives of people with AIDS through direct action, medical research, treatment and advocacy and working to change legislation and public policies).

There was also ACON’s Safe Sex Sluts who used impromptu guerrilla drag performances and camp theatrical antics when handing out condoms in bars, toilets and dance parties. The Safe Sex Sluts pushed a clear health message – “If it’s Not On, Then It’s Not On!” The condom at the time symbolised our struggle, it was our best and only form of queer survival. (ACON the AIDS Council of NSW, aims to end HIV transmission among gay and homosexually active men and promote the lifelong health of LGBTI people and people with HIV). These groups used agitation and random acts of passive resistance as a way of getting a social and political message through.

At the time there were also graffiti artists like Keith Haring who used their art-making to grab people’s attention, painting murals based on the political notion of HIV’s positive and negative symbolism, which at the time expressed an urgency and a message of queer survival and determination.

Today, in these times of Covid, it seems that the arts have been dropped into the “non-essential category”, underestimating the importance and role they can play both societally and individually. But art will survive and thrive under any conservative government – people cannot be silenced, they might go hungry but they will fight for their place at the dinner table.

Still from the film ‘Resonance’ (1991), supplied

How does dance help create resilience for minority groups, such as the queer community?

Art has always taught resilience. They go hand-in-hand. Every artist is stepping out into a space where they are using art to create story, reflect society, observe culture, and reflect their own personal view of the world. Our art lets people know we’re queer, we’re here – so get used to it.

My personal resilience has come from the queer punk perspective that anything goes – and every idea is worthy. That comes from lived experience from the streets. It informs the music I listen to and the books and philosophy I like to read.

I think queer dance floor culture and electronic music carve out a healing place for queer people to express their inner selves and thrive in a community of like-minded individuals. Sadly, Covid has smashed the dance floor as our sacred place of assembly – and to add another nail in the coffin, governments have made dancing illegal, while assembling at a sport event is ok, this makes no sense. Dancing in the streets will get you arrested.

Queer Sound Healing (QSH) which I have now become involved in as a writer and producer, creates a sense that we are more than just the mind. Many queer people have often felt ashamed by their body shape, or fervently frequent a gym in order to change the natural shape of their body. QSH uses narrative therapy to create a safe journey towards addressing our own unique survival needs, experienced in a time of queer trauma, HIV/AIDS, PTSD and internalised homophobia. This might sound like heavy material to immerse yourself in, however the experience is quite beautiful and uplifting. In QSH I use my knowledge of the human body through the many years of tantric yoga exploration and teaching, along with my experience and practice of urban spirituality.

Still from the film ‘Resonance’ (1991), supplied

What has the art-making meant to you personally?

I’m lucky I’ve never had to create art to please people and sell tickets, as one might have to running a major dance company. For my personal development, art-making is part of life itself. The arts can hold a space for working through embedded trauma, like the HIV epidemic. That’s why I have now started working with sound healing. From trauma can emerge incredible beauty.

I see life through the lens of queer-punk-individualism. I find the fringes of society are a great place to make art from. I do push back on heteronormative privilege, to remind people that we don’t all have the same human rights and that we still have to fight for ours. Our struggle is not yet over.

People are so aware these days of being politically correct, are we now losing the ability to look at things using humour, irony and campness? I find identity politics difficult to navigate. I do fear a very bland future lacking in the ability to see our universality as we hurtle towards the extinction of the planet and its finite resources.

Art-making in my view has the capacity to disrupt the status quo and reflect the times we live in. If we don’t have a utopia to strive towards, then I’m not really interested in a place at the table.

Mathew Bergan runs the Dancing Warrior Yoga Practice as well as Queer Sound Healing Workshops.

Mathew Bergan is the founder of Dancing Warrior Yoga school in Newtown, Sydney. He has a background in contemporary dance, choreography, sports massage, writing and film-making. He has been teaching Hatha yoga since 1993 and practices his own form of urban Spiritualism. He has studied somatic counselling is presently completed his post-graduation in Gestalt therapy. Mathew teaches yoga from Union Street Yoga, Erskineville, Sydney.

His next Queer Sound Healing is presented in the 2022 Mardi Gras festival titled: A Trip To Limerence, I’m not perfect, but I’m perfect for me.