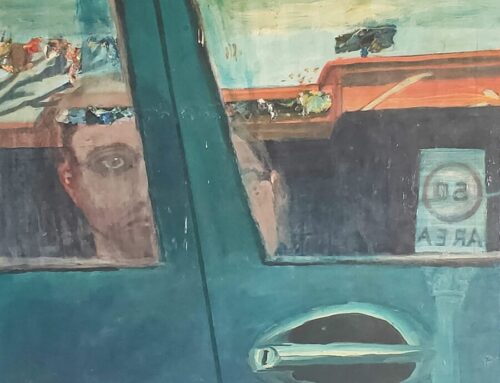

Armelle Swan is a Sydney based artist specialising in painting. She has a BFA (Hons I) and MFA from Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney. Formerly an emergency nurse, she gave up that career in the ‘90s to focus on her art; however, she considers her experiences in that role were seminal for later thinking and making. So, she brings to bear scholarly interests, such as the nexus of art and health in notions of visual thinking, brain, mind and neurology, to any making.

I have submitted two works. One is a self-portrait and the other is a painting of my daughter’s folded hands as she lay in her coffin. One morning in late 2018, my twenty-seven year-old daughter was found dead in her bed, most likely from a cardiac event, unleashing a torrent of grief.

‘Vicky’s hands’ (2020), oil on canvas

This painting is one of the first works made towards what will ultimately be a body of work on the subject of grief. As such, it marks the ‘front gate’, the approach, towards how I am processing this catastrophe and its myriad sequelae. The “front gate” idea came to me via the painting of Vicky’s hands, not the portrait. I had a mental image of her hands opening out, as if they were the two halves of a front gate at the main entrance.

Yet these paintings are not just as a personal navigation of meaning. I aim to explore the subject of human grief in contemporary society more broadly. So yes, it is a response to deep trauma, but I must add, it is given an extra dimension of the surreal by having been made during a pandemic-induced period of ‘suspension’ of normal life.

I will never feel entirely comfortable about this subject and the trauma that gave rise to it, but that merely underscores why it’s so important to make art from it. It is the best means by which I can process my tragedy. The trauma of sudden death, losing your child, is life-altering in the extreme, so it has inevitably influenced my practice. It has affected how and when I could return to work and the subject matter of that work. The brutal nature of the injury to mind, heart, soul, and body means that my art work is now imbued with the new, damaged version of myself as I negotiate the language of grief through making.

These works speak to death, the supreme bond between mother and child and, what I have now realised, is the culturally taboo subject of grief. Yet death is universal. Much could be said about this yawning gap in the knowledge, the scant literature on grief, the virtual absence of child-death imagery in contemporary society and as a result we are ill-equipped to process and heal from trauma.

To the extent that any kind of ‘healing’ is possible, art making is a crucial, active, ongoing part of the process. Non traumatised parts of the brain are energised. Also, occupying the studio environment itself is beneficial. As a special place, it is an important locus of respite.

I have experienced many profoundly stressful events throughout my life which have resulted in elements or symbols of those experiences being funneled into, woven through, or materialising as artworks. Making those works allowed my injured mind to acknowledge and allude to the trauma, but also to ‘find a place’ or somehow resettle or ‘archive’ those events, thus rendering them less painful going forward. In other words, making an art work that references the trauma via a symbol perhaps, a sign that stands in for the whole painful experience, permits memory of the trauma to be attenuated. Subsequently, this enables a kind of peace to exist around the memories.

In the process of making the work, the trauma-related subject could be unleashed in all its horror, having a cathartic effect, or it may be reframed to be much less dramatic. Either way, you gain personal agency over the effects of the trauma. Both the processes of making and how the concept is realised in that material work, combine to produce the beneficial effects. I think that is the Making Effect.

What I discovered in the immediate aftermath of the death was that I desperately wanted to be able to look at other artworks that might help me know and understand my own bewildering experience better. A great deal could be said about this alone but suffice to say an artwork, I believe, could ‘answer’ questions from the bereaved, such as ‘What am I feeling? How have other mothers been with their dead daughters?

What can I look at that helps me know what is happening? Where is my story told?

Armelle Swan

Making and thinking are intrinsic to my being. And critical to my wellbeing. These two activities are my way of being in the world and making sense of the human condition. I speak of my making as a range of activities which primarily involves painting, but also includes collage, drawing, writing and making assemblages. Meanwhile, I have found that writing a memoir in response to trauma, very much a creative act, has been immensely helpful in terms of coping and coming to terms with grief and loss.

More of Armelle’s work can be found at https://armelleswanartist.wordpress.com/